A vaccine is an immunobiological substance that is introduced into the body with the aim to confer specific immunity against a certain disease caused by microbes like bacteria and viruses.

Vaccines are either made up of whole and weakened or a component of the disease-causing microorganism, which mimics its infectious activity after entering the body, thereby stimulating the immune system to respond by signalling B cells to disease-specific antibodies. These B cells can recognise the disease-causing pathogen in case it enters the body again to cause an infection and can suitably respond by producing specific antibodies.

Depending on the type of vaccine, the mechanism defers but the principle of eliciting an immune response remains the same. Although in some vaccines, like live vaccines and killed vaccines, the actual disease-causing microorganism is introduced into the body in small doses, either after weakening or attenuation (live vaccine) or inactivation (killed vaccine), the risk of getting the infection is next to none.

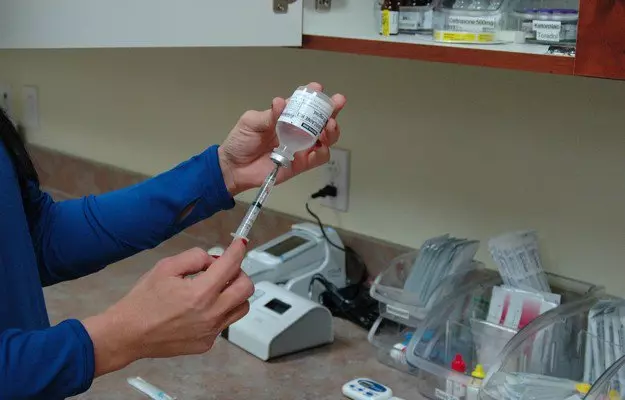

Vaccines are generally available in liquid form (or sometimes in powder form and have to be reconstituted with the appropriate fluid) and are typically injected or given as oral drops. Other means to give injections can include the nasal route. The method of vaccination depends on the type of vaccine and is generally not privy to changes.

Although the terms are often used interchangeably, immunisation and vaccination are, strictly speaking, not the same thing. Vaccination refers to the process of administration of a vaccine, whereas, immunisation is the body’s response to it as it develops protective antibodies and becomes immune to the pathogen. Immunisation is not exclusive to vaccines as preformed immunoglobulins (the medical term for antibodies) are used clinically for post-exposure prophylaxis or protection from infection after having been exposed.

Immunoglobulins are also used intravenously in autoimmune disease flare-ups and given to babies at birth for added protection from certain infections like Hepatitis B. Additionally, it would be beneficial to note that as part of routine childhood immunisation, children receive not only vaccines against infectious diseases but also Vitamin A.

Vitamin A is not a vaccine but it helps boost the body’s immune system response and create antibodies towards the vaccine, or immunogen, more efficiently. Additionally, to protect against the drastic, and sometimes fatal, consequences of vitamin A deficiency the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that high dose vitamin A supplements be given together with routine vaccines to children between 6 months and 5 years of age. The reason the two activities are combined is to increase coverage and ease the logistical burden. Immunisation, or vaccination, programmes can be routine for target vulnerable populations (like children, elderly, pregnant women, etc.), in case of special medical conditions (like after splenectomy) or in the case of emergency situations like outbreaks, epidemics or pandemics.

(Read more: Vaccines for newborns, infants and children)