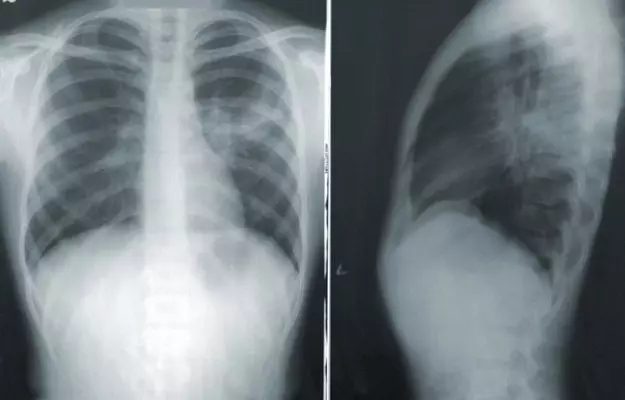

COVID-19 is known as a respiratory disease because the infection typically starts in the upper respiratory tract (nose and throat) and then moves down to the lower respiratory tract (windpipe and airways or bronchi and air sacs or alveoli of the lungs). Scientists looking into the after-effects of COVID-19 in recovering patients are now finding that the viral infection may permanently scar the lungs, causing a condition known as post-COVID fibrosis.

Here’s how this happens:

- The virus that causes COVID-19, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 or SARS-CoV-2, enters the body through the nose, mouth or eyes. Once inside, it typically travels to the lungs where it starts multiplying inside the alveoli (air sacs).

- As the body begins to realise an intruder is appropriating its resources, it fights back by putting up an immune response. This immune response has multiple levels to it. Even the most basic one, however, causes inflammation and triggers cells called fibroblasts which help in healing wounds. (Read more: Immune system and immunity)

- Normally, these fibroblasts do an excellent job of patching us up at the site of an injury by forming a scar (this process is known as scarring or fibrosis). However, if the injury is too big or if there are too many injury sites or if the injury is on a vital organ like the lungs, the scars can get in the way of the normal functioning of the organ.

- In the case of severe COVID-19, the moment the body detects the presence of the virus inside the air sacs (alveoli), it calls in immune cells like neutrophils and pro-inflammatory proteins called cytokines to deal with the infection. As immune cells and fluids go back and forth between the alveoli and blood vessels, the walls of the alveoli suffer a lot of wear and tear. The fibroblasts step in to repair the damage. However, instead of the specific lung parenchymal tissue that is perfect for allowing the exchange of gases with blood, the fibroblasts make collagen—the most abundant protein in the body present in all our connective tissues, skin, blood vessels, bones, in short, everything that gives structure to the body. While the collagen fibres can patch up the alveoli (through scarring or fibrosis), they make the alveoli walls thicker and more rigid, thus reducing their ability to function properly.

Scarring or fibrosis in the lungs is an irreversible process. Too much scarring means the lungs lose their ability to expand and contract, to let air in and out.

Researchers have found evidence of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) in the lungs and blood vessels of patients with severe COVID-19. These traps are web-like structures comprising neutrophil elastase and myeloperoxidase proteins that stimulate the production of more mucus and inflammation. (Autopsies of deceased COVID-19 patients have shown blood clots in almost all parts of the body, including the brain.) Now, researchers say that these NETs could be behind the formation of fibrin-rich clots in the blood vessels and lung damage. NETs can also trigger a cytokine storm in COVID-19.

Medical practitioners and researchers are now finding that this may happen to some recovering COVID-19 patients—a discovery that is not entirely shocking as severe COVID-19 is associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).

Indeed, ARDS—seen as shortness of breath and low blood oxygen (hypoxemia)—is often the cause of severe illness in COVID-19. Doctors already know about post-ARSD fibrosis. Similar to that, post-COVID fibrosis is large-scale scarring of the lung tissue as a result of COVID-19.

Read on to know more about this condition that could cause long-term damage to the lungs of recovered and recovering COVID-19 patients.